Pack Snacks, and Don’t Be Terrible—A Q&A with Sarah Hörst, Plenary Speaker at the 2022 Physics Congress

Spring

2023

Feature

Pack Snacks, and Don’t Be Terrible—A Q&A with Sarah Hörst, Plenary Speaker at the 2022 Physics Congress

James Hirons, Makayla Teer, Ryan Rodriguez, and Elyzabeth Graham, SPS Reporters, Texas A&M University - Commerce

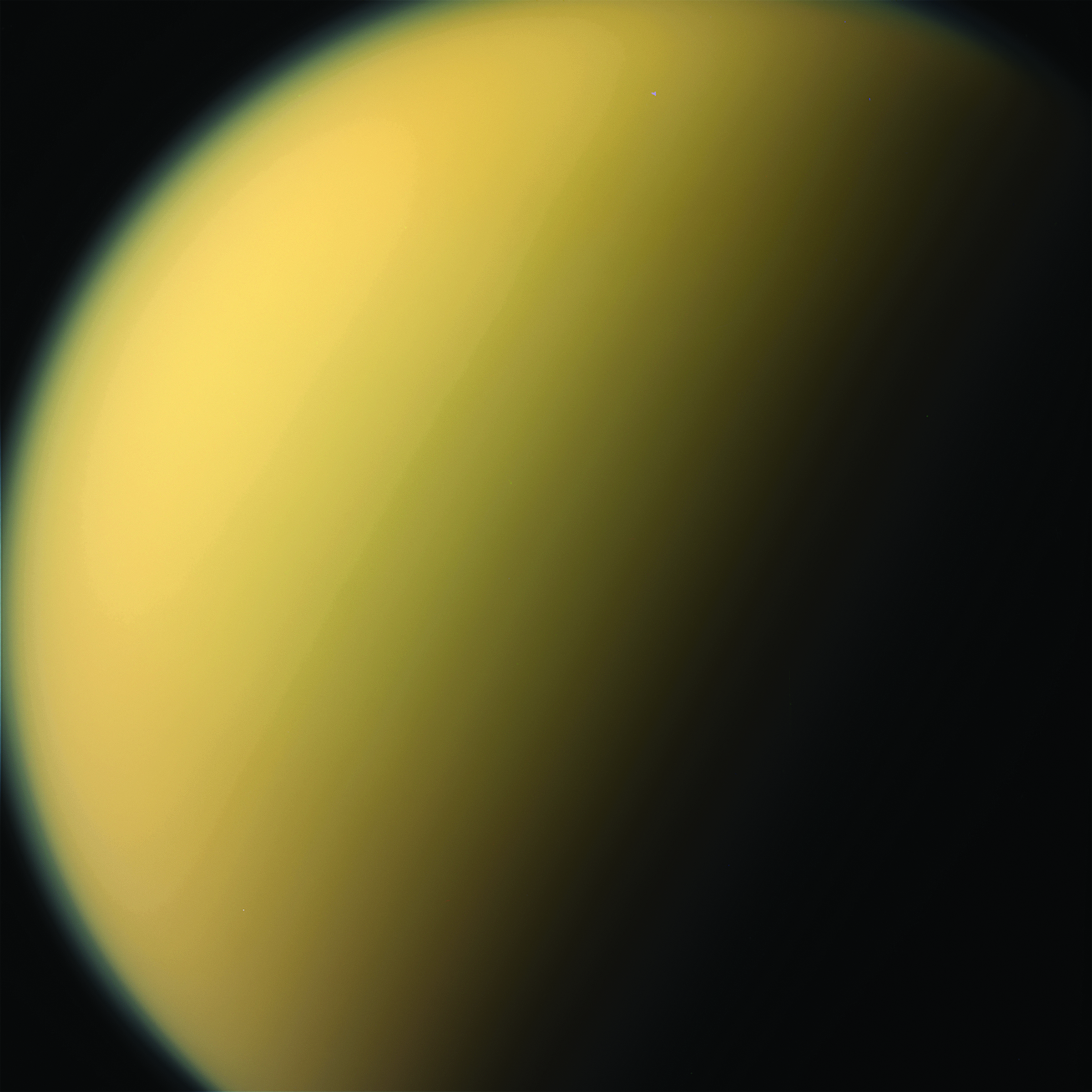

Sarah Hörst is an associate professor of earth and planetary sciences at Johns Hopkins University. She specializes in the complex organic chemistry occurring in the atmosphere of Titan, as well as elsewhere in the universe.

Who fostered your curiosity at an early age?

My parents. My dad was a doctor, and my mom had one of these fairly typical stories for women of her generation. She majored in biology and wanted to go to grad school, but that wasn't really a thing for women. When I was little, she had a bookstore.

My mom missed doing science so she started working at a small biological research institute. She was a research assistant because she only had a bachelor's degree. My mom went to grad school to get her PhD when I was seven and she was 41. She got her PhD when I was 13―I did the references for her dissertation. I would come home from school, and there'd be a stack of papers sitting next to the computer. I would just sit there and type in references for her.

Both of my parents were very into STEM, which was a big privilege and really helped make the path easier for me.

What was the driving force behind your pursuit of atmospheric chemistry?

I had done summer research with my undergrad advisor, looking at the Galilean satellites. During the school year, he sent me an email asking me to come by his office. I get in there and he starts buttering me up, “We have this project, and we immediately thought of you!” It turned out that I had to go to the telescope on campus every single night for like nine months, looking for clouds on Titan. Clouds on Titan are very bright. You don't even need to take pictures; you can just look at how bright Titan is to see if there are clouds.

Voyager flew by Titan and couldn't image the surface because the atmosphere was so thick. It’s this place that’s so interesting based on the few things that we know about it, but it’s so averse to giving up its secrets. From then on, I was really interested in Titan.

As a woman in STEM, what is the biggest challenge you faced during your educational career?

One thing that was really hard was the lack of role models. I went to Caltech for my undergrad. I didn't take a single class in my planetary science major from a female faculty member―not a single class. I took a total of two undergraduate STEM classes from female faculty members, one in mechanical engineering and one in physics. I also had

a literature major, and half of those professors were women. And it was like, “What message are you trying to send here?”

My class had the highest percentage of women that had ever been admitted to Caltech; we were 37 percent when we started and 25 percent when we graduated. In grad school it wasn't a lot better. Every single one of our core classes was taught by a male faculty member. I was 25 or 26 before I took a class from a female planetary scientist.

There were two female faculty members in my PhD department. Neither one of them―and this is not a knock on them―was living a life that I envisioned for myself. I was thinking, “Okay, so these women who are complete badasses and amazing are doing this thing, but they're not doing it the way that I want to. Is there room for me?”

I didn't work for a woman until my postdoc. That was such a game changer for me. She was doing science the way that I wanted to. It wasn't cutthroat. It wasn't competitive. It was us in her office looking at data and laughing. When we're learning, we model the behavior we see from other people. If you don't have a person to model yourself after, it’s a lot harder to figure out how to do what you want to do.

What is the best piece of advice you've been given in your career?

The first thing that comes to mind is to make sure you pack snacks.

One of the things that my undergraduate research advisor helped me to see early on is that being happy is really important.

What changes would you like to see in the physics, astronomy, and planetary science community?

That one's easy. We need to fix our issues with diversity and inclusion 1,000 percent. We are selfishly missing out on talent, and that's preventing us from doing the things that we say we want to do. But more from a human perspective, we need to not be so terrible.

What do you wish someone had told you earlier in your career or education that you want students to know?

It's going to be okay, whatever that means. It's true—it will be okay.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Got Snacks?

SPS provides $300 in financial support for chapters to start food cabinets for hungry physics and astronomy students. Chapters use funds for items that are freely accessible to all department undergraduates and are encouraged to fundraise to restock and maintain the food cabinet. Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. For details see spsnational.org/scholarships/FFHPS.

Be a Role Model for Physics and Astronomy Students

Join the SPS and Sigma Pi Sigma Alumni Engagement Program—a database of participants willing to be speakers, panelists, tour guides, and mentors for SPS chapters. Learn more at spsnational.org/programs/alumni-engagement.

Help high school physics classes understand the joys of studying physics and astronomy and the career opportunities they provide—sign up for Adopt-a-Physicist! Physicists are "adopted" by up to three classes and interact for a set, three-week session, making lively, in-depth discussions possible. Learn more at sigmapisigma.org/sigmapisigma/adopt-physicist.