Sharing the Spotlight: Resources for Correcting the Narrative of Physics History

Spring

2020

Feature

Sharing the Spotlight: Resources for Correcting the Narrative of Physics History

Hannah Pell, Research Assistant, American Institute of Physics Center for History of Physics

If I asked you to think of a famous physicist, who would come to mind? Newton or Einstein? Maxwell, Kepler, Bohr, Heisenberg, or Feynman? Physics curricula often recount the history of the discipline as the accomplishments of several individuals, as if their contributions built the science from the ground up.

But this story is incomplete. By focusing solely on the discoveries of a few, we overlook all of the physicists whose work inspired and informed the more famous discoveries. We also ignore the important role of collaboration and community in making scientific progress, and the fact that progress—and the historical record of progress—unfolds within social, historical, and cultural contexts. When we direct the spotlight only on the towering heroes of physics, we lose sight of the valuable contributions of so many others, especially scientists from groups that have traditionally been underrepresented in their fields.

As physicists, we can play an important role in changing the outdated narrative of our history—and of who physicists are and can be. One way to do this is by intentionally incorporating the stories of traditionally overlooked physicists into our classrooms, outreach events, and lectures.

The Center for History of Physics (CHP) at the American Institute of Physics has a collection of over 50 free teaching guides that use interactive and hands-on activities to highlight little-known scientists who have made invaluable contributions to physics and related sciences.

Written by SPS interns in collaboration with history of science graduate students, the teaching guides highlight the contributions of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ figures in physics history. In many cases, their stories are told through oral history interviews, archival photographs, historical documents, and personal correspondence. Most of the guides are designed for high school classrooms, but the activities can be easily adapted for younger audiences, science outreach events, and community programs.

Incorporating often-ignored physics history in outreach events can help us correct misperceptions about physicists and portray a more accurate picture of how we arrived where we are today. Additionally, situating scientific discoveries within historical contexts emphasizes the dynamic interplay between physics and society. Lessons from history provide insight into the culture of physics, and by highlighting traditionally overshadowed figures in physics history we can cultivate a more equitable, supportive, and inclusive physics community today and in the future.

Here are a few examples of lessons that—quite literally—shine a light on physics history.

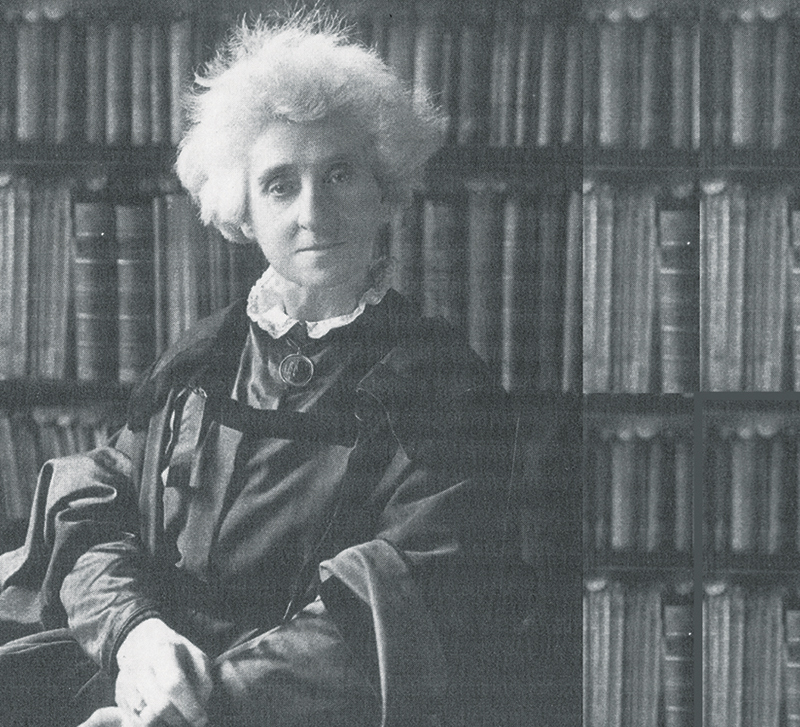

Spectra and Margaret Huggins

Margaret Huggins was a 19th-century astronomer who, alongside her husband, advanced spectroscopy as an analytical technique for identifying the chemical makeup of astronomical objects. In this lesson, students learn about Huggins and explore the emission spectra of different elements using diffraction glasses. They investigate how spectroscopy can be applied to astronomical objects and consider the status of 19th-century astronomy.

Margaret Huggins was a 19th-century astronomer who, alongside her husband, advanced spectroscopy as an analytical technique for identifying the chemical makeup of astronomical objects. In this lesson, students learn about Huggins and explore the emission spectra of different elements using diffraction glasses. They investigate how spectroscopy can be applied to astronomical objects and consider the status of 19th-century astronomy.

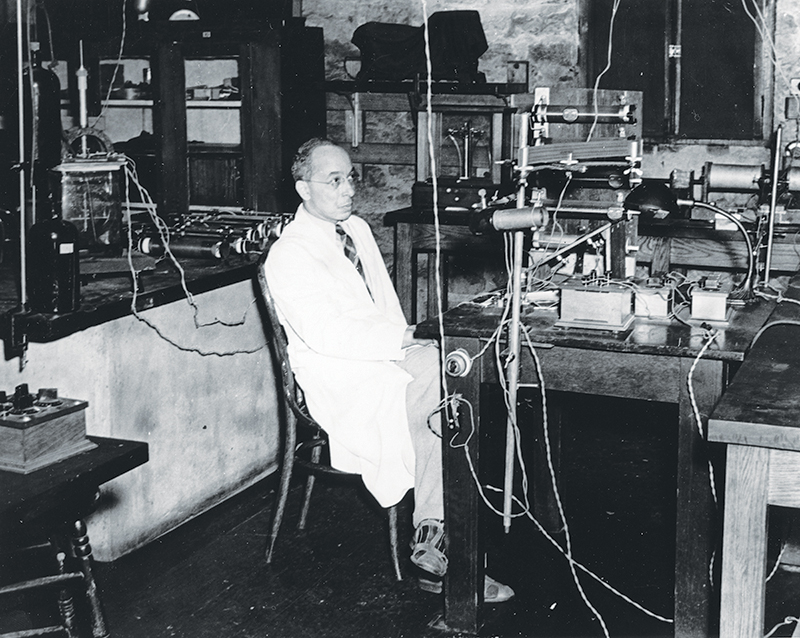

Elmer Imes and Spectroscopy

Elmer Imes received a PhD in physics in 1918. He was only the second African American to receive a physics PhD, following Dr. Edward Bouchet in 1876. Imes made important contributions to the field of infrared spectroscopy, the study of how molecules absorb and emit infrared light. In this lesson, students learn about Imes’s life and work while exploring how light refracts through a prism and how this relates to spectroscopy.

Elmer Imes received a PhD in physics in 1918. He was only the second African American to receive a physics PhD, following Dr. Edward Bouchet in 1876. Imes made important contributions to the field of infrared spectroscopy, the study of how molecules absorb and emit infrared light. In this lesson, students learn about Imes’s life and work while exploring how light refracts through a prism and how this relates to spectroscopy.

Victor Blanco in Chilean Skies

Victor Blanco was a Puerto Rician astrophysicist who navigated international politics to forge the way for observatories and research centers. He played a formative role in the Cerro-Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a United States observatory in Chile. Blanco’s research focused on star classification and the Milky Way’s structure. In this lesson, students discuss the relationship between science and politics, and practice identifying astronomical objects in a sky survey.

Victor Blanco was a Puerto Rician astrophysicist who navigated international politics to forge the way for observatories and research centers. He played a formative role in the Cerro-Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a United States observatory in Chile. Blanco’s research focused on star classification and the Milky Way’s structure. In this lesson, students discuss the relationship between science and politics, and practice identifying astronomical objects in a sky survey.

All of the lesson plans are freely available on the Center for History of Physics website: www.aip.org/history-programs/physics-history/teaching-guides-women-minorities