Applied Physics, Grand Boulevards, and the “Social Dimension”

Spring

2018

Elegant Connections in Physics

Applied Physics, Grand Boulevards, and the “Social Dimension”

Dwight E. Neuenschwander, Southern Nazarene University

“Science and technology, like all original creations of the human spirit, are unpredictable… We can rarely see far enough ahead to know which road leads to damnation. Whoever concerns himself with big technology, either to push it forward or to stop it, is gambling in human lives.”1

In early 1934, 29-year-old German architect Albert Speer received his first major commission. Not only was this commission an irresistible opportunity for a young professional seeking a big break, but it also changed Speer’s destiny—and eventually the lives of millions of people. The commission came from the new chancellor of Germany, Adolf Hitler. For the next eight years in his role of chief architect, Speer was drawn into Hitler’s inner circle, working closely with his famous client, who had seemingly unlimited resources. Speer was to design the “architectural megalomania” of grandiose palaces, monuments, and oversize public buildings that Hitler envisioned for Berlin as the centerpiece of the Third Reich’s empire.

In February 1942 Hitler changed Speer’s portfolio, appointing him minister of armaments and war production. As the war turned against Germany, to maintain factory production schedules Speer became complicit in using slave labor from occupied countries. At the Nuremberg trials following the war, Speer was sentenced to 20 years in Spandau prison. “I waived the right to an appeal,” he recalled. “Any penalty weighed little compared to the misery we had brought upon the world.”2

In prison he reflected over his decisions and actions, what he saw and what he had chosen not to see. The memoir of this technically savvy Third Reich chief architect and minister of armaments and war production closes by recalling excerpts of the speech he was allowed to make at Nuremberg. There he had offered a dismal assessment of technology’s leverage in human affairs. While advances in technology bring so many obvious advantages to civilization, they do not necessarily measure advancement towards a civil society, as Speer observed:

The criminal events of those years were not only an outgrowth of Hitler’s personality. The extent of the crimes was also due to the fact that Hitler was the first to be able to employ the implements of technology to multiply crime.

I thought of the consequences that unrestricted rule together with the power of technology—making use of it but also driven by it—might have in the future. This war… had ended with remote-controlled rockets, aircraft flying at the speed of sound, atom bombs… In five to ten years it would be possible for an atomic rocket, perhaps serviced by ten men, to annihilate a million human beings in the center of New York within seconds.… The more technological the world becomes, the greater the danger.

…As the former minister in charge of a highly developed armaments economy it is my last duty to state: A new great war will end with the destruction of human culture and civilization. There is nothing to stop unleashed technology and science from completing its work of destroying man which it has so terribly begun in this war.…3

Concerning unleashed technology’s ability to destroy mankind, common ground could be found between the Nazi’s minister of armaments and a refugee who left Germany to escape Nazi brutality. In a 1950 open letter published in Science which was addressed to the newly formed Society for Social Responsibility in Science, Albert Einstein wrote, “In our times scientists and engineers carry a particular moral responsibility, because the developments of military means of mass destruction is within their sphere of activity.” 4 Two years later Melba Phillips, alarmed that research agendas were being driven by military applications, described a sad irony in the same journal. “The greatest humanitarian opportunity ever offered to science,” Phillips wrote, “namely, the technological development of vast backward areas of the earth—has become manifest and realizable in our epoch.…[But this] has received only the most paltry governmental support and is largely ignored. What has replaced it? A vast program of military research, which transforms the humanitarian aim of science into its opposite…” 5

The weaponization of physics did not begin with DARPA, the Manhattan Project, or the Peenemünde V-2 factory. In a 1991 speech to a conference of physics teachers, Freeman Dyson described the “six faces of science”: three ugly faces and three beautiful faces. Two of the ugly faces of science are its being “tied to mercenary and utilitarian ends, and tainted by its association with weapons of mass murder.” 6 If physicists had their way, weapons of mass murder would never be the goals of physics research any more than the domestication of animals was intended to produce the horseback-mounted marauding Scythians who plundered the agricultural surpluses of settled peoples.7

The weaponization of physics says more about human nature than it does about physics and technology. We must live with the bitter but unavoidable reality that from the beginning of mankind’s adventures with technology, weapons have always been a priority of applied physics. According to spurious legend, in 212 BCE, Archimedes supposedly set enemy ships afire through the applied geometrical optics of “burning glass” mirrors. Even though that event probably never happened,8 that so early a tale of applied physics emphasizes destruction illustrates the point. Even our revered Galileo found it necessary to shrewdly market his slide-rule-like calculator as a “military compass.”9 Some things never change.

Such realities illustrate the “law of unintended consequences,” which “twists the simple chronology of history into drama.”10 The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unintended consequences of the innocent desire to understand how nature works within the nucleus. As intellectual companions of those who stumbled across nuclear fission when following that desire and as intellectual companions of those who, under duress but with great cleverness, quickly turned that discovery into effective weapons, we can empathize with Ted Taylor’s feelings on the dilemma presented by these weapons’ seductive glitter and dark consequences:

The trait I noticed immediately was inventiveness… “If something is possible, let’s do it,” was Ted’s attitude. He did things without seeing the consequences. So much of science is like that.

Driving away from the lights of Santa Fe and up into the mountains towards Los Alamos, Taylor fell into a ruminative mood… “I thought I was doing my part for my country.… I no longer feel that way… The whole thing was wrong. Rationalize it how you will, the bombs were designed to kill many, many people. I sometimes can’t blame people if they wish all scientists were lined up and shot.” –Stanislaw Ulam, recalling Ted Taylor11

Speer’s point about the downsides of technology also apply beyond the existential threat of nuclear weapons, extending to technologies in everyday life. He gloomily observed,

The nightmare shared by many people [is] that someday the nations of the world may be dominated by technology—that nightmare was very nearly made a reality under Hitler’s authoritarian system…12

Hitler’s dictatorship was the first dictatorship of an industrial state in this age of modern technology... By means of such instruments of technology as the radio and public-address systems, eighty million persons could be made subject to the will of one individual.… The instruments of technology made it possible to maintain a close watch over all citizens…13

He concluded, with some pessimism, that technology can, itself, become a kind of dictatorship. But he also saw the remedy, here as against all dictatorships, in people demanding their autonomy:

Every country in the world today faces the danger of being terrorized by technology…Therefore, the more technological the world becomes, the more essential will be the demand for individual freedom and the self-awareness of the individual human being as a counterpoise to technology…14 Dazzled by the possibilities of technology, I devoted crucial years of my life to serving it. But in the end my feelings about it are highly skeptical.15

One wonders what Speer would say about technology’s rule over us today, such as automation that deskills people16-18 and makes workers unemployable;19-20 social media that promises connections but delivers isolation;21 half a dozen all-powerful corporate overlords reaching into every corner of our lives22; technology creep, perpetual noise, and endless distractions that leave little space for thoughtful reflection; 18, 23-26 or the “close watch” of ubiquitous surveillance and Big Data.25-26

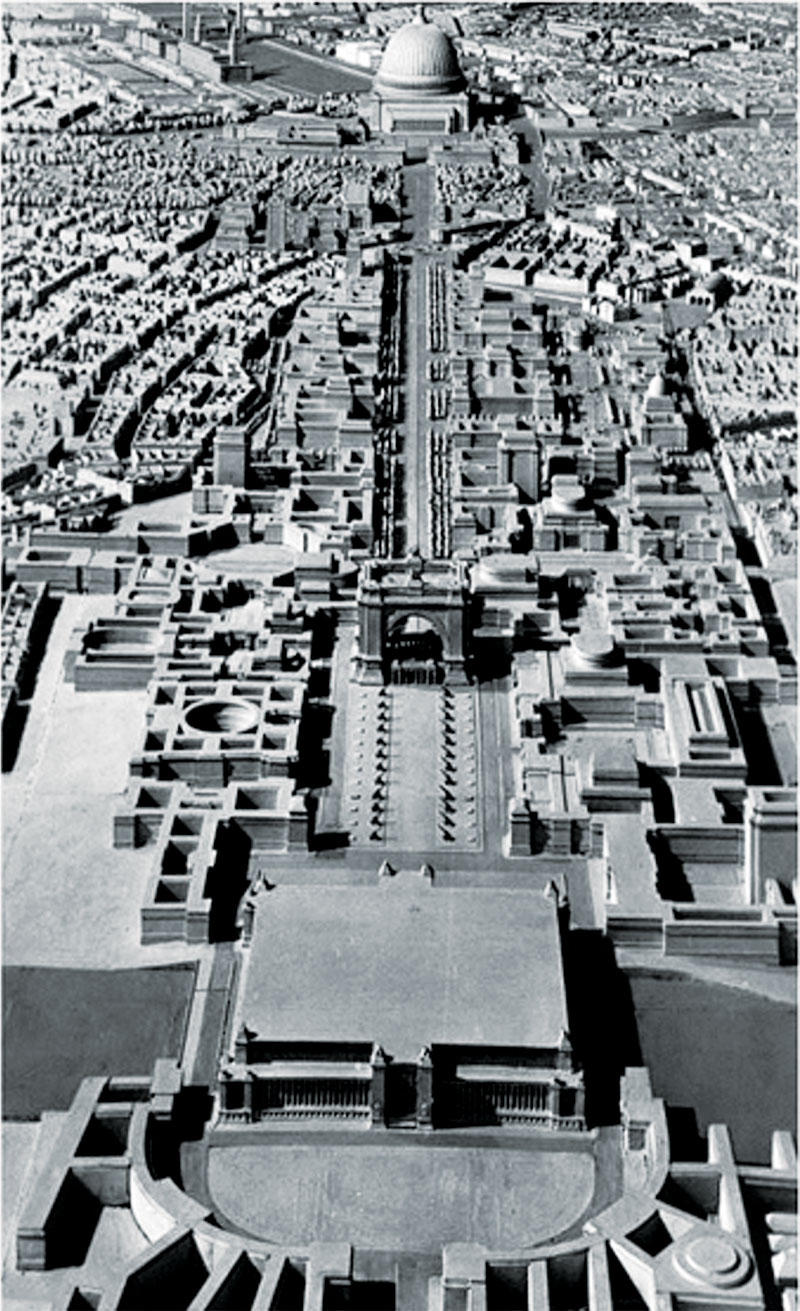

In 1936 Hitler enlarged Speer’s architectural commission into the task of redesigning Berlin. Hitler envisioned spectacular monuments that would remind future generations of the Reich’s greatness, as surviving architecture bears witness to ancient Rome’s achievements. He insisted on a wide, three-mile-long central boulevard in Berlin, featuring at one end a colossal arch three times the height of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and at the opposite end a great dome reaching seven hundred feet to the globe-topped summit, enclosing 16 times the volume of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Hitler was so focused on his monuments that he overlooked the everyday needs of the city’s inhabitants. As Speer tried to work into the magnificent triumphal boulevard mundane but essential concerns such as traffic flow patterns,

[Hitler] would look at the plans, but really only glance at them, and after a few minutes would ask with palpable boredom: “Where do you have the plans for the grand avenue?” Then he would revel in visions of ministries, office buildings and showrooms for major German corporations, a new opera house, luxury hotels, and amusement palaces… His passion for building for eternity left him without a spark of interest in traffic arrangements, residential areas, or parks. He was indifferent to the social dimension.27

We physicists and astronomers are passionate about learning the deep secrets of nature and using them to fuel innovation. Do we have grand “boulevards” of our own? Do we assume that because we revel in the marvelous technical applications made possible by physics that everyone else will love them too? To take an example, people have been concerned about automation and robots making human beings unemployable since the dawn of robotics.16,19-20, 28 Yet automation and robotic development continue with unleashed acceleration, suggesting that its most enthusiastic advocates may have chosen not to see its human costs in the social dimension.

We might take a lesson from events in the history of physics that were contemporary with Speer’s architectural drawings of the Berlin that never was. A few years ago some students in my Science, Technology, and Society (STS) class wrote to Professor Dyson and asked him, “What do you consider to be science’s biggest mistake?” His reply, which emphasized the social consequences of a physics discovery, was immediate:

Science’s biggest mistake happened in 1939 after nuclear fission was discovered, before the beginning of World War Two. The physicists could have organized an international meeting of experts to discuss the problem of nuclear weapons, as the biologists did in 1975 when the sudden discovery of recombinant DNA made genetic engineering possible. The biologists agreed on a set of rules to ban dangerous experiments, and the rules have been effective ever since. The physicists could have done something similar in 1939, and there was a good chance that nuclear weapons would never have been built. But the chance was missed. Once World War Two had begun in September 1939, it was too late, because the scientists in different countries could no longer communicate.29

In a recent meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Mark Frankel, director of the AAAS Scientific Responsibility, Human Rights and Law Program, urged all scientists to think more deeply about their social responsibilities. He reminded his colleagues, “The communities in which you live and the communities much farther out…are ultimately affected by the work that you do.”30

Because of the law of unintended consequences, we cannot foresee all the effects of our work, even in the communities where we live. Even so, what responsibility do we bear for influencing research applications towards humanity-affirming rather than humanity-diminishing ends? Like addicts, do we feel compelled to do something just because we can, without seeing the consequences? I do not know the answers to these questions. Perhaps appreciating the questions is more important than answering them. Perhaps living within the questions could point to useful guiding principles. Scientists are supposed to look at new ideas with a critical, peer-review eye. That means we have to care. A student in a recent section of the STS class articulated this important insight:

Some preliminary discussion [in class] has caused me to think about who we are as human beings…Humans are increasingly being replaced by machines in the workforce, much like how horses were replaced with the advent of the automobile and tractor…

So, I have wondered, does anything make humans special? While wrestling with this, I have considered one thing that sets humans apart from machines: We have the ability to care… Autonomous boats could theoretically have searched for survivors of the flooding in Houston [from Hurricane Harvey], but they could not have cared about those they saved like the human rescuers certainly did. Machines would be motivated by code, not a sense of morality…31

Evoking Robert Pirsig, the real business of applied physics is caring.32 Our ethical responsibilities as physicists go beyond the obligation to maintain the truthful practices whereby professional trust is earned.33

Our work inevitably touches the lives of everyone outside our profession, too. Physics can tell us what is, but physics cannot tell us what we ought to do. In a 1939 speech Albert Einstein made this point clear: “Objective knowledge provides us with powerful instruments for the achievements of certain ends, but the ultimate goal itself and the longing to reach it must come from another source. And it is hardly necessary to argue for the view that our existence and our activity acquire meaning only by the setting up of such a goal and of corresponding values.”34

May we not get so focused on our grand boulevards that we forget the citizens who have to live with them, for better and for worse. When implementing the values of human creativity and initiative that drive innovation, let it not be at the cost of other human values such as self-reliance, individual freedom, self-awareness, personal adventure, identity, empathy, and caring. All these values, working coherently together, are necessary for the human experience to be a journey of fulfillment. Our responsibility as scientists and engineers goes beyond being clever and doing accurate technical work. The skepticism we routinely practice over claims in a physics paper should also be applied to the glowing promises of promoters of the widget du jour who have their own agendas. Our responsibilities include, in an essential way, slowing down to thoughtfully reflect over potential consequences and caring enough to make sure we are never “indifferent to the social dimension.”

Deep appreciation is extended to STS students across 30 years for their questions and insights on these topics, and to Professor Freeman Dyson for his wise, gracious correspondence. Thanks to Brad Conrad whose insightful and helpful suggestions improved this article.

1. Freeman Dyson, Disturbing the Universe (Basic Books, New York, 1979), 7.

2. Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (Macmillan, New York, 1970), 618.

3. Ibid., 615.

4. Albert Einstein, Ideas and Opinions (Three Rivers Press, New York, 1954, 1982), 26.

5. Melba Phillips, “Dangers confronting American science,” Science 116 (Oct. 24, 1952), 439–443.

6. Freeman Dyson, “To teach or not to teach,” Am. J. Phys. 59 (June 6, 1991) 490–495.

7. Jacob Bronowski, The Ascent of Man (Little, Brown, & Co., Boston, 1973), 79–80.

8. See MythBusters Episode 46, “Archimedes’ Death Ray,” https://mythresults.com/episode46.

9. Jacob Bronowski, ref. 7, 200.

10. Theodore White, In Search of History: A Personal Adventure (Harper & Row, New York, 1978), 304–306.

11. John McPhee, The Curve of Binding Energy: A Journey Into the Awesome and Alarming World of Theodore B. Taylor (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York, 1974), 120.

12. Albert Speer, ref. 2, 615–616.

13. Ibid., 614–615.

14. Ibid., 616

15. Ibid., 619.

16. Nicholas Carr, The Glass Cage: Automation and Us (Norton, New York, 2014).

17. Matthew Crawford, Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work (Penguin Books, New York, 2009).

18. Mark Bauerlein, The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future (Penguin Books, New York, 2009).

19. Norbert Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society (Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, 1954).

20. “Humans Need Not Apply,” YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Pq-S557XQU.

21. Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other (Basic Books, New York, 2011).

22. See Farhad Manjoo, “Tech’s Frightful Five: They’ve Got Us,” NY Times, May 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/10/technology/techs-frightful-five-theyve-got-us.html; “How Five Tech Giants Have Become More Like Governments Than Companies,” National Public Radio interview on the program Fresh Air, October 26, 2017; transcript at https://www.npr.org/2017/10/26/560136311/how-5-tech-giants-have-become-more-like-governments-than-companies.

23. Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (Norton, New York, 2011).

24. Matthew Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York, 2015).

25. Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (Crown, New York, 2016).

26. “Every step you take: As cameras become ubiquitous and able to identify people, more safeguards on privacy will be needed,” The Economist (Nov. 16, 2013), 13.

27. Albert Speer, ref. 2, 93.

28. The Robot series of Isaac Asimov [including I, Robot (1950), The Caves of Steel (1953), The Naked Sun (1957), The Robots of Dawn (1983), Robots and Empire (1985)] explores the relationships between humans and robots and morality when robots do all of the work and much of the thinking. If robot labor was an option in Speer’s armaments factories, one wonders what would have happened to the people who were forcibly taken as slave laborers from occupied countries.

29. Dear Professor Dyson: Twenty Years of Correspondence Between Freeman Dyson and Undergraduate Students on Science, Technology, Society and Life, D. E. Neuenschwander, ed. (World Scientific, Singapore, 2016), 141.

30. Elisabeth Pain, “The social responsibilities of scientists,” Science (Feb. 16, 2013), http://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2013/02/social-responsibilities-scient....

31. Travis Vernier, essay for Science, Technology, and Society course, September 5, 2017, Southern Nazarene University. Used with permission.

32. Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values (Morrow, New York, 1974, 1999), 35.

33. Jacob Bronowski, Science and Human Values (Harper and Row, New York, 1956, 1965).

34. Albert Einstein, ref. 4, 42.